In fantastical tales, where normal expectations are upended, writers get a chance to offer strange and unsettling ideas and let the reader make their own interpretations. Sometimes it’s difficult to know who to have empathy for; the main protagonist, the titular character or someone else entirely?

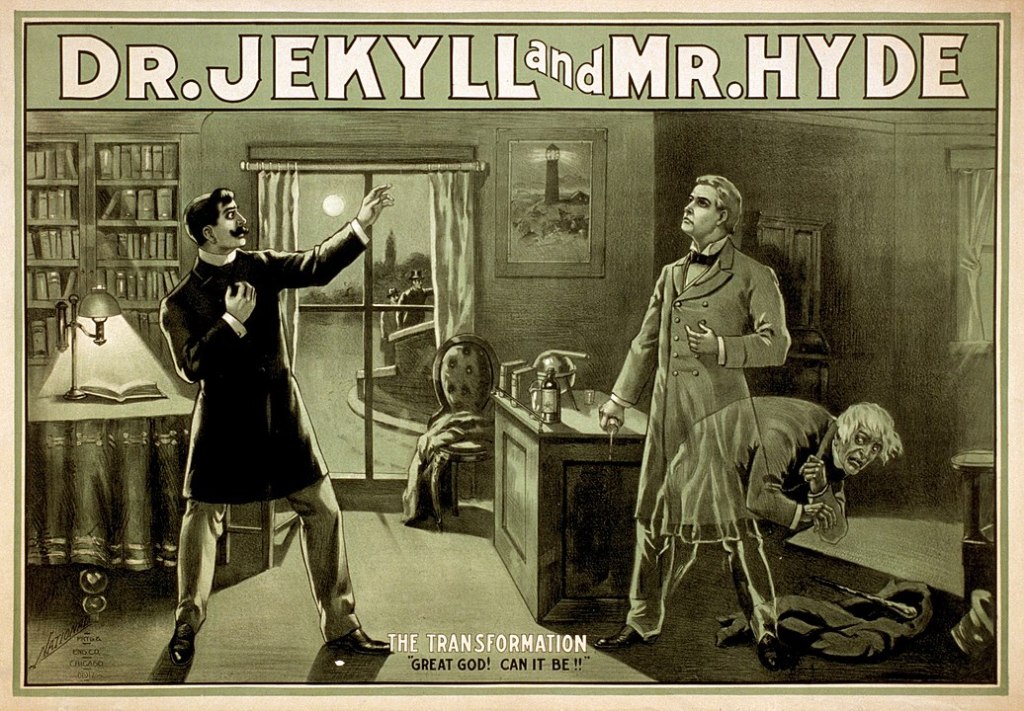

One example of this is in the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde the 1886 novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. This is a story about an unpleasant looking, dangerous, and violent man called Mr Hyde, who is, unexpectedly, an associate of the respectable of Dr Jekyll, who in turn is a friend and client of the narrator, Mr Gabriel Utterson.

The story shows Utterson trying find out more about Mr Hyde and bring him to justice for his heinous crimes. But it soon becomes clear that Mr Hyde [spoiler alert if you haven’t read it!] is Dr Jekyll! The reader discovers that Jekyll has drunk a serum that allows him to be a completely different person from the one who has high moral public standards publicly. In this new version of himself as Mr Hyde, Jekyll can indulge in unstated vices (one can only assume violence and sex?) without fear of detection and being publicly shamed and held to account.

It appears that Stevenson’s inspiration may have been from his own friendship with an Edinburgh based French teacher, Eugene Chantrelle, who was convicted and executed for the murder of his wife in May 1878:

“Chantrelle, who had appeared to lead a normal life in the city, poisoned his wife with opium. According to author Jeremy Hodges,[5] Stevenson was present throughout the trial and as “the evidence unfolded he found himself, like Dr. Jekyll, ‘aghast before the acts of Edward Hyde’.” Moreover, it was believed that the teacher had committed other murders both in France and Britain by poisoning his victims at supper parties with a “favourite dish of toasted cheese and opium“(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Case_of_Dr_Jekyll_and_Mr_Hyde)

Clearly this heinous crime should not be celebrated, but Stevenson could see the fictional possibilities when a reputable person could still have such a dangerous, secret, other personality. This strange idea, of one human being two people, obviously intrigued Stevenson.

But why was Stevenson so drawn to the ‘Strange’? Was it partly because he suffered from severe bronchial trouble for much of his life and would have spent many hours sick in bed daydreaming or having night terro rs? Was it also from a childhood of being told stories and then telling his own? His father, a leading lighthouse mechanic, who approved of his story telling and encouraged him. And from his nurse Alison Cunningham, whose stories revolved around her strict Calvinist beliefs and folk tales, which gave young Stevenson nightmares, but also kindled his interest in ‘strange’ stories.

Stevenson would often have to stop going to school entirely because of illness and had private tutors instead. He was a very skinny, odd looking child and had trouble getting on with other students as a result. This may have led to him feeling like an outsider. He kept writing despite this, or perhaps because of it, and his books like Treasure Island and Kidnapped and his poetry are still in print. The sense of being an outsider is important in ‘strange’ or gothic stories. The outsider is often malformed physically, mentally or morally and is shunned or cast out and wreaks their revenge as a result.

“I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend”

The lament of Dr Frankenstein’s ‘monster’

Which leads us to the other notable teller of classic strange, or gothic fiction, whose most famous novel was written 68 years before Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde strode into the public imagination. This was, of course, Mary Shelley and Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus.

Published in 1818, but begun when Mary was just eighteen. Her mother, the great writer and women’s rights advocate, Mary Wollstonecraft, had died 10 days after giving birth to her, so she was almost born from death, a terrible legacy for any child. After Mary lost her own her first child, the book was finished by the time she was nursing her second and pregnant with her third. All these pregnancies and the begetting of life and the loss of life meant Mary was well used to how fragile what we create can be.

When her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned after a sailing trip got into difficulties in a big storm in 1822, Mary was only 25, had lost three babies and was once again on the sharp end of death.Mary already knew about being an outsider. She had run away with Shelley and was perusing a writing career like her late mother, knew women writers were looked down upon and treated badly by publishers and the public.

That is why, ,originally, she didn’t give her name to Frankenstein and later, when she did, she had to suffer accusations that a man, possibly her dead husband had written it. Victor Frankenstein is the creator of the nameless ‘monster’.

But it was Mary who created them both and the reader could sympathise not just with Victor, the brilliant scientist, but also with his monster who is doomed to live without purpose and meaning. He is the ultimate strange outsider, and possibly Mary was musing on the great privilege it is to give life whilst knowing the difficulties of living a healthy, happy life?

Like Stevenson, who died at 42, Mary did not live a long life, dying at 54 from a brain tumour. But both left seismic novels that still intrigue, entertain, and inspire many years after their deaths.

Quite surprising and, yes, very Strange!